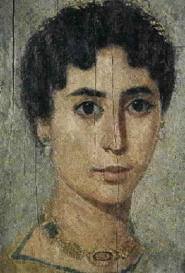

This was inspired by the life of Hypatia, who lived in the 4th and 5th centuries C.E. She was a real person and brilliant mathematician. Often she is the only woman mathematician mentioned in books on the history of math. The character writing is fictitious, but the events are true.

A Day in Alexandria

I arrived in Alexandria as the sun was going down. The trip from Cyrene had been a rough one and I was glad to have my feet on solid ground again. My teacher and mentor, Synesius, had corresponded with her for years. He raved about her brilliance, her inventions, her ability to teach others, and her original mathematical work. Hypatia! Finally, I would hear for myself. Little did I know what horrors I would witness and how the world would change from this year on.

This was my first trip to the great city of Alexandria. I planned to be here for a while to take advantage of the magnificent library (at least what was left of it) and many great teachers. I would eventually find a place to stay, but for now, I had a letter of introduction to a friend of my mentor. He very kindly invited me into his home and gave me a meal and place to sleep for the night. The political climate is very tense these days. It is the year 415 (A.D.) and the Christians are gaining strength in many places. They have very little tolerance for beliefs different from theirs. Cyril, the church patriarch, considers anyone of the neo-Platonic school of thought to be a heretic. But, there are still many of us who are members of this school, including Hypatia.

As we sat down to a simple meal, or rather reclined in the Greek fashion, my host began to tell me a little more about the city and Hypatia.

“You know her!”, I cried.

“Actually, I’m a friend of the family. More her father’s friend.” He replied.

“Please tell me. Are all the stories I hear of her true?”

He laughed, “Actually, many of them are, but what in particular are you interested in knowing?”

“They say she inspires great devotion in her students and anyone interested in learning.”

“She does. She’s a magnificent orator, devoted to teaching, and to the truth. I make sure that I hear her often and read most of what she writes. She has done quite a bit of original work in mathematics, written commentaries and built on the works of some of the greats – Diophantes, Apollonius, among others. ”

“And she is a scientist as well,” I added. “My mentor, Synesius, has been particularly interested in her inventions, such as the astrolabe and the planesphere for studying astronomy.”

“I know nothing of that field, but am told that she has a number of inventions that have added to it. I am more familiar with her writings in mathematics, although, she is very learned in many fields. Her father, Theon, my friend, was determined to produce the ‘perfect human being’ as he says. Many think that he has. Of course, he is a professor of mathematics at the university as well, so he had access to many resources and took charge of her education. I’m sure she picked up the love of mathematical elegance from him, but he didn’t stop there. She learned it all – astronomy, astrology, mathematics, religion. And he didn’t neglect the body. She is accomplished at rowing, swimming, horseback riding . And yes, she is very beautiful as well, even now in her mid 40s. She has also traveled extensively and basically made a name for herself.”

“Did you say she studied religion?”

“Yes, as in ALL religions, rather than one. Theon was particularly concerned that she NOT be caught up in any one religion to the exclusion of new truths. He feels that all dogmatic religions are false. If we can’t be open to new ideas, we have cut ourselves off from the truth. Hypatia has been raised to be very discriminating in her thoughts and acceptance of new ideas. As Theon frequently says, ‘Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all.’ . . . It hasn’t made it easy for her in the current climate. She is a close personal friend of Orestes, the prefect. I think that is one reason that her popularity is tolerated. But, ever since 412, when Cyril became patriarch, things have become more and more tense. Sometimes I fear for her and others who are seen as champions of other ways of thought.”

“She must be an amazing person. Is she married?”

“She is very beautiful, but no, she has never married. She has had opportunities, but always says that she ‘is married to the truth.’ But, I think you’re a little young for her,” he teased.

I was embarrassed, but still had to ask. “Do you think I could meet her?”

“Hmm . . . I think she has a gathering at her home tomorrow night. Her students often gather there and anyone is welcome. Right now though, it is getting late, and her lecture is the first of the day tomorrow. I had planned to go with you, but won’t be able to if I can’t get any sleep.”

I was the one who had trouble sleeping that night because of my excitement. I was up with the sun and after a brief meal, we set out toward the university. It was a beautiful day as we walked along the bay. The sun was bright and the colors were vivid. It was a perfect complement to what I felt inside. We followed the coast for just a short period before we turned to go up to the main thoroughfare that led to the University of Alexandria. As we approached, it became noisier and more crowded as I expected. When we got closer, however, it seemed to be more of a mob than the usual crowds of a city.

“What is happening?” I asked my new friend.

“I’m not sure. This is unusual. I have friends who live here. Let’s go in and see if we can go up to the roof to get a better view.”

We were allowed entrance by one of the slaves who recognized my host and told us that the master was already on the roof observing. As we joined him, I could see that the street was crowded by an angry mob. In the center of the mob was a woman in her chariot. The crowd had brought the horse to a stop and was attacking the woman, hitting her, grabbing her hair, and throwing stones. I could already see where a clump of her hair had been pulled out. She was fighting back, but it was useless against so many. Someone yelled above the crowd, “to the church, to the altar.” At that point, strong hands grasped the woman and she was carried into the nearby Christian church.

“The poor woman, what can we do? Do you know who she is?”

“That,” whispered my host, “is Hypatia. . . I doubt we can do anything against that mob to help her, but we can try. I know a back way into the church.”

As we raced to the door, fear seized my heart for this woman I had never met, but heard so much about. The mob of people, mostly men, were obvious as Christians by the way that they dressed. I understood that they didn’t favor her teachings, but this anger seemed extreme.

We were unable to get through the door until it was too late. When we did, the extent of their depravity was overwhelming. The mob, whom I later learned was a group of monks from a monastery in the desert, had stripped her and peeled away her skin with bits of tile and pottery. Her limbs had been torn from her body. Her voice was silenced.

I couldn’t stay in Alexandria after that. It wasn’t really safe for a non-Christian foreigner, and besides, I didn’t have the heart for it. I heard rumors later about what had happened. Some said that Hypatia’s limbs were put on display in different parts of the city; some said her body was burned. Orestes fled and Cyril finally had what he wanted – power. I went to Athens to continue study, but everywhere things were changing.

Note: Although partially destroyed in 391 C. E. the library in Alexandria would be completely destroyed a few years after Hypatia’s death and the western world would be plunged into a period that has come to be known as the dark ages.

Carl Sagan speaks about Alexandria and Hypatia:

References

Hubbard, Elbert. Little journeys to the Homes of Great Teachers. Vol.23. New York. The Roycrofters. 1808.

Mlodinow, Leonard. Euclid’s Window: The Story of Geometry from Parallel Lines to Hyperspace. New York. Simon and Schuster. 2001.

Osen, Lynn. Women in Mathematics. Cambridge, Massachusetts. The MIT Press. 1974.